From Muscle to Memory: The New Jew and the Physical Rebirth of Jewish Identity

How Jewish athleticism has evolved since the state of Israel’s birth

By Adam Poupko

Original image by Brooke Cohen-Pinsky

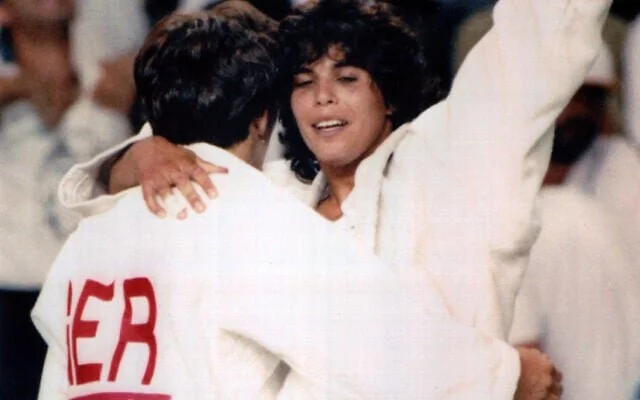

Cloaked in her judo robe, Yael Arad stepped onto the podium as the crowd roared with the Israeli flag raised above her head. Placed around her neck was a silver medal, a reminder that she is among the top three in the world in women’s judo. As she accepted the medal and second place in the judo competition at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, she simultaneously achieved a feat of profound national significance. She became the first Israeli athlete to ever stand on the Olympic podium since the establishment of the state of Israel.

Israeli Olympic judoka Yael Arab, right, celebrates and hugs her German opponent Frauke Eickoff after winning the semi-final match at the Barcelona Olympics, on July 30, 1992. (AP Photo)

Becoming the first Israeli athlete to win a medal was far from just a personal achievement. It was a gift of purpose for Jewish athletes across the globe, giving them a collective cause they could all compete under: a flag representing their faith. The path to the podium for Arad was a modern culmination of a deliberate, 100-year-old project to physically transform the Jewish identity.

As Jewish populations grew across Europe in the 19th century, they lived among widespread antisemitic stereotypes. Historian Sander Gilman mentions in his book “The Jew’s Body” that many European residents viewed the Jews as physically weak, tending to be more bookish and less active in outdoor activities. Gilman notes that Europeans would also often frame Jewish differences using medicalized terms, and believed they exhibited characteristics like pale skin, bad posture and urban existence. Jewish physicians were trying to fight this antisemitic rhetoric at the time, but were met by the constraints imposed by the scientific rhetoric. These European stereotypes were gradually internalized, compelling Jewish communities to re-evaluate their own physical and cultural self-conception. This rhetoric would be unchanged until the Zionist movement established a new vision.

Max Nordau, co-founder of the Zionist movement, believed the source of this crisis was the exile from the land of Israel, as he stated in his speech at the Second Zionist Congress in 1898. Nordau envisioned a Jewish rebirth grounded in strength and health and rooted in the land, coining the term “Muskeljudentum,” or Muscular Judaism. A nation that aspires for a land cannot be based on a foundation of weakness, he argued, so the Jewish body needed to become a renewed site of embodying strength, discipline and vitality. This train of thought empowered Jews to believe that they could become more athletic and active in their lives, regardless of the European stereotypes that told them otherwise.

Many Jewish athletic associations were founded worldwide to support the growing recognition of Jewish athletic ability. Movements like Maccabi, established in 1929, cultivated a collective practice of sport, gymnastics and competitions. Others, such as HaShomer and Betar, extended the project to younger generations and broader reaches. Bodily training became linked to the defense of settlements and the preparation for political independence.

Chairman D.R. Sonnenfeld opened the gymnastics competition in 1919 in Brno, Czech Republic. (Margalit Sonnenfeld)

The evolving image of the diasporic, bookish Jew to the farmer-soldier marked the developing association of Jewish life with sovereignty, labor and strength. Todd Presner, in his book “Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Body and the Politics of Regeneration,” argued that the body became a political text, reflecting both the anxieties of modernity and the aspirations that Zionism brought with its idea. As the Jewish people strengthened their muscles, they simultaneously built a better future for themselves.

With Muskeljudentum providing the blueprint for this new identity, sport became the most visible embodiment of it. In the context of Zionism, athletics were not just a fun activity. It was a civic ritual, a public performance with symbolic enactments of nationalism. Within the kibbutzim, in schools and later in military training, the structured physical activity laid the foundation of a body that mirrored the aspirations of the emerging state. It was a civic religion that instilled habits of strength, collectivity and endurance for the next generation of Jews.

The new ethos became amplified through the visual sphere. Posters, photographs and early state propaganda consistently celebrated athletic figures, illustrating strong and sunlit bodies that worked the land by day and marched in formation by night. The Maccabiah Games, established in 1932, were a notable example of organized competition that presented this new idea as an effort to represent Israel on a global stage.

Delegates from different countries attend the opening ceremony for the first Maccabiah Games in 1932. (Israel State Archives)

They encapsulated the zeitgeist of the New Jew: Jewish athletes from around the world coming together to display physical abilities that symbolized unity and sovereignty.

Although revolutionary, the embodiment of the New Jew could be viewed as performative, for it was a deeply gendered expression of nationhood. The figures that dominated the posters and the people who filled the parades were almost always male. While most women participated in physical labor and collective life, they were often framed at the time as supporters rather than as athletic subjects, and their bodies were seen within the context of motherhood or agriculture. Despite the masculine prototype, the Zionist roots of the New Jew crafted a modern identity for Jews that was rooted in strength and belonging that applied to everyone, regardless of gender.

Today, many of these foundations have changed. Israel’s economy and daily life are now shaped more by technology startups than by tractors. This shift toward technology-based work raises questions about the continuing relevance of the New Jew ideal, as Israel has moved toward a model of strength defined more by innovation than by agricultural labor.

Few areas of Israeli life reflect the original archetype, but the athleticism associated with military service remains a notable exception. The act of serving carries a social prestige among Israelis, and male combat soldiers often represent the masculine image that was once tied to labor and sport in the early days of Zionism. However, many groups, including Mizrahi Jews and women, are pushing the margins in the Zionist narrative, challenging the meanings of belonging in Eurocentric, male-dominated spheres. Existing within the systems predominated by masculine ideals, they diversify the modern interpretation of what Jewish athletics represents. The ideal of the New Jew has not been abandoned for a completely different vision. It has been reinterpreted, more contested and more plural than it was in its original form.

Today, Jewish athletes are reaching new heights in the world of sports, ranking among the top competitors globally. In the NBA, Deni Avdija is making waves as the leading scorer for the Portland Trail Blazers, while here in Gainesville, the Gators’ men’s basketball team, under Jewish and Israeli head coach Todd Golden, captured a historic national title this past season. Jews have established a significant footprint across the sports world, a feat that seemed impossible decades ago. The future for Jewish athletes is at an all-time high and is expected to continue growing.

Adam Poupko is a junior journalism student at the University of Florida and a student assistant at the Bud Shorstein Center for Jewish Studies. He is a huge sports fanatic obsessed with basketball and the San Antonio Spurs, who is looking to make a name for himself in the sports writing industry as a Texan-Israeli.