When Nothing Means Everything

How the Holy of Holies encapsulates Jewish monotheism

By Rina Rodriguez

Original art by Molly Seghi

One of the most fundamental Jewish beliefs is the concept of a single, eternal, all-knowing God. It is a philosophy shared among all three Abrahamic religions, which, according to a 2020 Pew Research Center report, comprise more than half the world’s population. In the United States, even among adults who are not religiously affiliated, 70% of responders said they believe in some concept of a higher power. Note that they do not claim to believe in multiple higher powers, but rather, a single, indefinite force.

Amongst these large statistics, Jews stand at only 0.2% of the global population—a minute representation of those who subscribe to monotheistic ideas. The simple fact is that in today’s world, there is no novelty to a shapeless, indefinable God. That is the archetypal God, the Merriam-Webster God, the simple-word-association God. The “Jewish God” is unexclusive and commonplace—and simultaneously, an elegant statement on divine transcendence.

It would be a great mistake to judge the Jewish perception of God based on modern-day sentiments alone. Judaism has survived for centuries and maintained these same beliefs even in a polytheistic-dominated world, long before the term “monotheist” was coined. The Greco-Roman period is a standout example. In a world of pantheons of specialized gods, the Jewish nation stood out with its single, aniconic God. What made them even more unusual was not only their lack of participation in image-based worship, but their rejection of it as a sacrilegious attempt to quantify God.

This precept that Jews hold is counterintuitive when closely examined. Humans are visual creatures. We keep pictures of our loved ones in wallets, on phones and in offices. In the United Kingdom, it is customary to hang portraits of the reigning monarch in public buildings. The US does similarly with photographs of the president in federal government buildings. An image of God should be the most natural thing, especially when one believes that He is the supreme being of the world. One could argue that it is necessary to forge a tangible connection with Him.

Throughout history, the general Jewish population has grappled with these challenges. In the Book of Exodus, the story of the golden calf began when the Jewish nation requested Aaron to make “a god who shall go before [them]” (Exodus 32:1). It’s not a god who surpassed any realm of relatability, but a god they could easily place before themselves, its finitude comfortably within their framework of understanding. The Book of Judges is filled with cyclical stories of the Jewish nation turning to serve local deities before a leader ultimately guided them back to their one God. Something was appealing about these other gods, even if they never gained permanent legitimacy within Judaism.

By the Greco-Roman period, Jews held a strongly anti-image approach to their God, in line with the second commandment prohibiting idols. Tacitus, a Roman historian, recounts in “Histories” that when Roman Emperor Caligula planned to erect a statue of himself in the Second Temple, the Jews immediately organized mass demonstrations and prepared for rebellion.

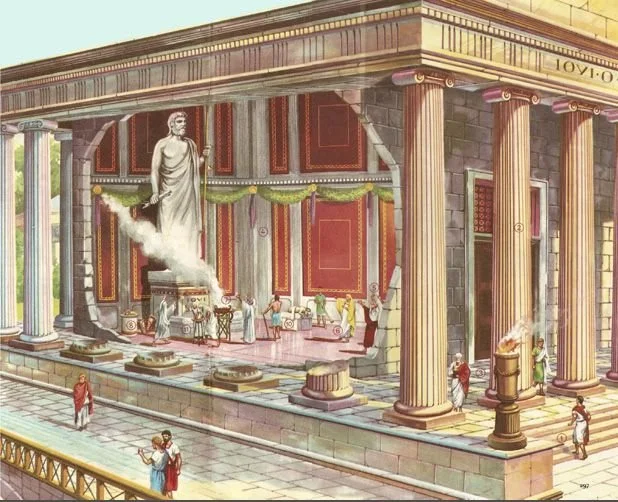

Offerings being brought into a Roman temple, with a statue of their god as the focal point. (The Worlds of David Darling)

By the Greco-Roman period, Jews held a strongly anti-image approach to their God, in line with the second commandment prohibiting idols. Tacitus, a Roman historian, recounts in “Histories” that when Roman Emperor Caligula planned to erect a statue of himself in the Second Temple, the Jews immediately organized mass demonstrations and prepared for rebellion.

So strong was the sentiment that an image of another being would be a desecration of their faith. These tensions nearly escalated into war and were only settled with the cancellation of the project following Caligula’s death.

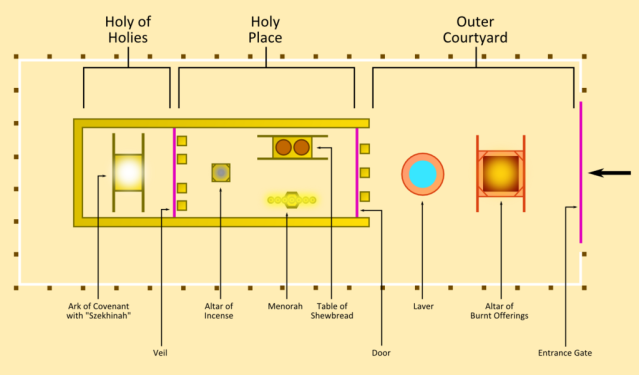

Perhaps the best and most consistent representation of this approach is the Holy of Holies, the primary resting place of God in Jewish tradition. But when Pompey and his soldiers entered the room, they found no representation of God within. Tacitus writes that since this incident, the impression of the Holy of Holies was “the secret shrine contained nothing.” It is worth noting that while the First Temple housed the Ark of the Covenant in the Holy of Holies, this artifact was absent from the Second Temple. For Pompey and his soldiers, the sanctuary of the Jewish God displayed not even the slightest notion of divinity.

Diagram of the Mikdash, which included the Holy of Holies. While the Ark of the Covenant was present in the First Temple, it was absent from the Second one, which Pompey entered. (Life-Giving Words of Hope & Encouragement/Chaplain Jeff Davis)

Pompey was not the only Roman to display confusion when faced with the Jews’ strange faith. Emperor Julian held more forgiving views, according to Guy Stroumsa’s “The Idea of Semitic Monotheism: The Rise and Fall of a Scholarly Myth,” maintaining that Jews and Romans “[differed] from one another either not at all or in trivial matters,” but still found an outstanding peculiarity in the Jews’ worship of a single God. Other criticisms labeled Jews as completely irreligious. Juvenal, in his work “Satires”, found them to “worship nothing but the clouds,” an attack on their God’s substantiality.

Louis H. Feldman, scholar of Hellenistic civilization and ancient Jewish life, found in his article “Origen's "Contra Celsum" and Josephus' "Contra Apionem": The Issue of Jewish Origins” that other pagan writers, including the notorious anti-Jewish grammarian Apion, went so far as to label Jews as atheists. This description seems completely antithetical to Jews and their devotion to God, so it is important to separate this word from its modern connotations.

Rome did not think Jews denied the existence of a higher power, but rather feared their mysterious, undefined God as a threat to social order and an insult to their national identity. Feldman explains that they did not hate heresy so much as an absence of patriotism. To Jews, their contestation of Caligula’s statue was a defense of their religion. To the Romans, it was an affront to their emperor’s authority, a demeaning insistence on placing a flimsy and absent god before their larger-than-life emperor. Their tendency to self-isolate and refusal to participate in pagan rituals was a rejection of their culture, fostering feelings of distrust and fear among the Roman populace. At the root of it, what Rome could not understand about Jews and their intrinsically seditious religion was the exact bewilderment Pompey and his soldiers encountered in the Holy of Holies: the incorporeality of a single God.

We have already established that the Jewish aniconic God is counterintuitive, was often abandoned in favor of idols and excluded the Jews from the polytheistic world. So what exactly is the appeal that allowed this belief to prevail until today, where it has become the most mainstream notion of God?

Jews found greatness precisely in God’s inability to be captured. A god that can be touched with human hands, seen with human eyes and described in human language is unworthy of worship. The limited access to and emptiness of the Holy of Holies was a perfect summation of this perspective. To understand the essence of God is inaccessible to humans, and attempting to represent his infinitude in a finite vessel is impossible.

L.E. Goodman, an American philosopher, points out in his book “God of Abraham” how even Moses, who in Exodus was said to “speak face to face” with God, was unable to see his true form. What Pompey and his soldiers took for simple nothingness was the Jewish statement that nothing in this world could hold a candle to their God.

This perspective, of course, creates a struggle in how Jews are supposed to understand what it is they worship. Maimonides, a prolific Jewish writer and philosopher, held the opinion that “he who knows God best can see most clearly his transcendence of the predicates used in our common language.” Goodman explains this to mean that the closest understanding of God is achieved through acknowledging that it is futile to try to describe him.

That does not mean that attempts are never made. Jewish texts are filled with anthropomorphic descriptions of God meant to demonstrate His relationship with those who follow Him. The prayer Avinu Malkeinu translates to “our father, our king,” signifying the duality of His behavior as both a king worthy of respect and a father who demonstrates compassion. In the Torah, He assumes the descriptors of angry, jealous, loving and forgiving as easily as one slips off a coat. For a religion that rejects depictions, Judaism heavily employs imagery. Its prevalence, Goodman found, prompted Maimonides to encourage parents to educate their children from the earliest possible age that God is not a person, despite the use of metaphors in their education. At the root of it, imagery and anthropomorphism are supplements in Jewish theology used to explain the nature of God. God Himself remains fundamentally indefinable.

The increased popularity of monotheism we see today is not because God has suddenly become easier to understand. It is not the factory-setting religious belief, either. The single, aniconic God remains transcendent and incomprehensible. His lack of depiction is not a lack of recognition, but a statement that it is impossible to try to represent God with something that He far surpasses. Today, Jews understand this lack of representation as something that strengthens their relationship with God. Prayer, Torah study and performing mitzvot are traditionally recognized as the primary ways to foster a personal connection to God, none of which require an understanding of His form. Jewish monotheism has survived throughout the political persecutions, fluctuations in faith and conflicting anthropomorphism for one reason. Ultimately, God’s worthiness of worship is inextricably tied to his transcendence.

Rina Rodriguez is a freshman industrial engineering student at the University of Florida and a freelance writer for “V’nishma.” She is particularly passionate about Sephardic Jewish life after the expulsion and the survival of Jewish communities throughout the world.